Take a trip to Lindisfarne in Northumberland, the peaceful Holy Island connected to the mainland by a tidal causeway, where the islanders live their lives based on the rhythm of the tides.

* This site contains affiliate links, where I get a small commission from purchases at no extra cost to you.

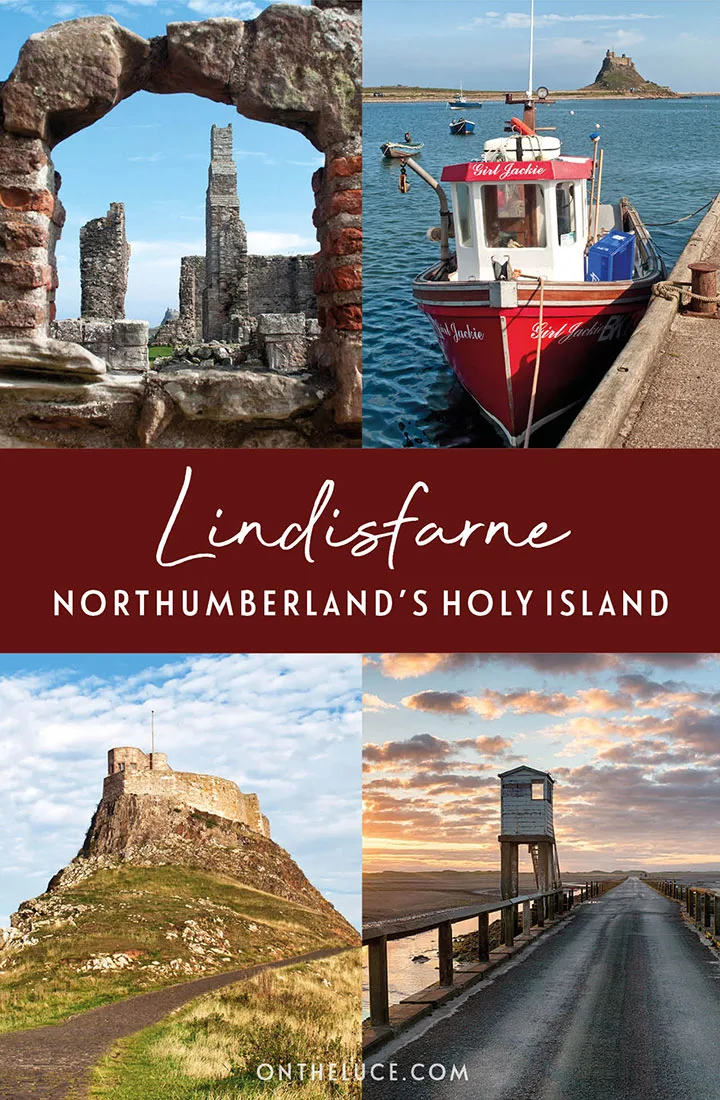

Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island, in Northumberland is a tiny island with an important religious history. Despite only being 3 miles long and 1.5 miles wide, it was the heart of Christianity in the Anglo-Saxon period, and home to St Oswald and St Cuthbert.

Lindisfarne is still a place of pilgrimage today, and has kept a peaceful, magical atmosphere. Add in a castle, ruined priory, church, winery and beautiful wild, windswept coastal scenery, and it makes a great day trip if you’re visiting Northumberland.

But what makes visiting Lindisfarne so unusual is that it’s completely cut off by the tide twice a day. A narrow causeway links the island to the mainland, but when the tide is in it’s inaccessible. So the islanders have learnt to live their lives based on the rhythm of the tides, and visitors have to slow down and work with nature if they want to visit the island.

This post tells you everything you need to know to visit Holy Island, from how to tackle the tides to get there to what to see on the island and where to eat, drink and stay.

How to get to Lindisfarne

Working out how to get to Holy Island takes a bit more planning than most places thanks to the tides. Twice a day the island is cut off from the mainland by the sea, so you need to plan your trip around the tide times. The latest tides are listed on the Northumberland Council website, and are handily colour-coded with green safe times and red no-go times.

Sometimes the tides work out so you have a perfect daytime, 9am–5pm slot to visit Holy Island. But that’s unusual – often the crossing times mean you have to fit a visit into the early morning or late afternoon and will only have a few hours to explore.

If you’re staying in the area for a few days, it’s worth checking the tides in advance and planning the best day to visit Lindisfarne, as the tides can change by an hour each day. And although most people visit the island at low tide, that’s not the only option.

When we visited Northumberland, the tides meant the island was cut off from 12pm–5pm. So rather than squeezing a quick trip in early in the morning, we decided to stay on the island while the tide was in and maroon ourselves on Lindisfarne for the afternoon.

The advantage of staying on the island at high tide is that it’s quiet and peaceful, with mainly locals around. You’re more likely to see wildlife like seals as the sea is nearer the shore. Some cafés and shops do close during high tide, but pubs are normally open.

Holy Island by car

If you’re travelling by car, the entrance to the causeway is well signposted off the A1 near the Lindisfarne Inn. It’s 10 miles south of Berwick-upon-Tweed, 57 miles (70 minutes’ drive) from Newcastle or 68 miles (1.5 hours) from Edinburgh.

The Holy Island Causeway was built in 1954, and is a normal tarmac road, running across the bay. The speed limit is 60mph, though most people go slower to soak up the views.

At low tide it’s hard to imagine that the road gets covered by up to five metres of water. But appearances can be deceptive, as the flatness of the land means the tide comes in very quickly. Drivers to often get caught out, despite all the warnings. However powerful you think your car might be, it’s nothing compared to the power of the oceans.

If you do manage to get stuck then there’s a wooden hut up a ladder – like a mini lifeguard’s shelter – where you can wait out the tides (though it probably won’t do your car much good) if you don’t want to fork out the £6000 it costs for a helicopter rescue.

Once safely on the island, road access is restricted into the village, so visitors are asked to park at the Chare Ends car park just outside (TD15 2SE). The car park is pay and display, and starts from £5 for three hours (you can pay with cash, card or by phone).

Keep an eye on the clock and make sure you allow plenty of time before the tide comes in. Often there’s a lot of traffic trying to leave the island at the same time, especially during the busy summer season, so getting out of the car park can be slow going.

Holy Island by bus

You can also visit Lindisfarne by public transport using the Borders Buses 477 bus. This runs from the train station in Berwick-upon-Tweed to Holy Island and takes 35 minutes. The timetable varies depending on the tides so you need to plan in advance – particularly in winter when bus services normally only run on Saturdays and Wednesdays.

Or you can visit Holy Island without a car on a full-day guided tour* from Edinburgh, which also includes a visit to Bamburgh and a tour of Alnwick Castle and Garden.

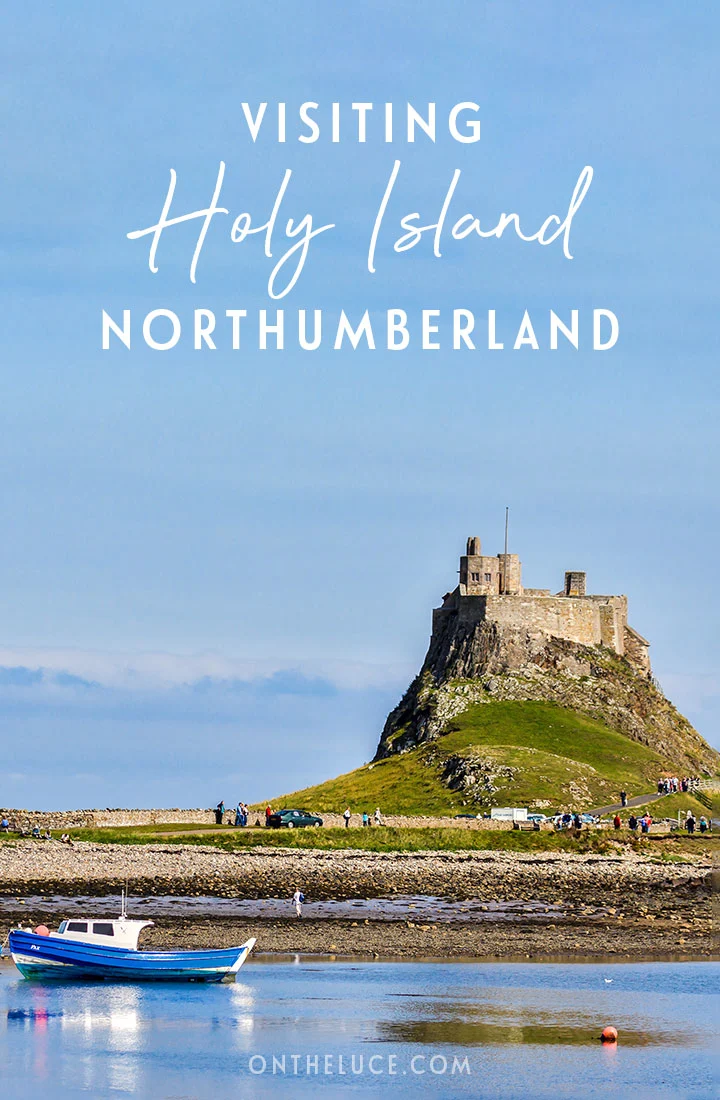

Holy Island by boat

Another way to reach Lindisfarne is by boat. Boat trips run from Seahouses and sail around the Farne Islands, where you can spot seals and seabirds, before going ashore on Lindisfarne at high tide, with two hours to explore the island before returning to the mainland. Scheduled trips only run May–October, and timings are dependent on the tides.

Holy Island on foot

Or you can follow in the footsteps of the pilgrims by walking the Pilgrim’s Way to Holy Island. This route has been used by worshippers since 635 AD – and everyone else until the road was built in 1954. The walk is three miles long and takes 75–90 minutes.

The route is different to the road, and is marked by poles in the sand. You should only attempt it when the tide is going out (the timing isn’t the same as for cars, so safe walking times need to be calculated separately – check this guide). Beware that the route is muddy so wear shoes you don’t mind getting dirty, or do it the pilgrim way and go barefoot.

Things to do in Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne Priory

The first monastery on Lindisfarne was founded by Irish monk St Aidan in 635 AD and it became an important Christian pilgrimage site. It was home to St Cuthbert, who’s commemorated by a statue among the ruins. And the illustrated Lindisfarne Gospels – now on display in the British Museum – were written by monks here in 710–725 AD.

But after a series of Viking attacks in the late 8th century, the monks packed up the Gospels and Cuthbert’s body and relocated to Durham. The priory was rebuilt in the 12th century, and it’s those ruins you see today, destroyed in the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

The site is run by English Heritage and entry is free for members.* Although all that’s left are the arches and walls – including the Rainbow Arch which survived the collapse of the tower above it 200 years ago – you can get a feel for the original scale of the priory.

There’s also a museum with Anglo-Saxon and Viking finds on display. And behind the Priory is The Lookout, a former coastguard tower with views over the island to the mainland. On a clear day we could see as far as Bamburgh Castle and the Cheviot Hills.

St Mary’s Church

St Mary the Virgin Church is the island’s parish church, and dates from 1180–1300, making it the oldest building on the island. It also incorporates part of an original Saxon church and was later extended by the monks who rebuilt the priory in the 12th century.

Inside you can see stained glass windows, altarpieces and a wooden sculpture by Fenwick Lawson called The Journey. This shows a group of hooded monks carrying St Cuthbert’s coffin off the island when they left after Viking raids in 793. And outside there are some pretty flower beds which are covered with colourful blooms in spring and summer.

Lindisfarne Castle

Set on a rocky crag, Lindisfarne’s castle towers over the flat expanse of the rest of the island. The castle was built in the 16th century and is one of a series of castles around this area that protected the English border from Scottish and Viking invaders.

It was first built as a fort, using stone from the priory after it was destroyed in the Dissolution of the Monasteries. It was a lookout for soldiers and the coastguard, but later became the holiday home of the Edwardian owner of Country Life magazine, Edward Hudson. He had it renovated in Arts and Crafts style by his friend, architect Edwin Lutyens.

The site is run by the National Trust and entry is free for members. You can still see some of Lutyens’ original interiors, when the castle was divided up to replicate a country house. There’s also a walled garden, sheltered from the worst of the island winds, which was designed by Gertrude Jekyll and still uses the original 1911 planting scheme.

Lindisfarne Village

Lindisfarne village is the heart of this island community, with stone cottages, shops, cafés and pubs (see below for some recommendations). There are only around 160 permanent residents on the island, but it gets over 650,000 visitors a year.

The Lindisfarne Heritage Centre in the village is worth a visit if you’d like to find out more about the island. This small museum has displays on different periods of local history, from the early Christians and Vikings to more modern island life. You can also see an interactive copy of the Lindisfarne Gospels and learn about how they were made.

There’s also a free exhibition about the lifeboat station which used to protect Holy Island (they now come from the mainland) at The Old Lifeboat House on St Cuthbert’s Beach.

St Aidan’s Winery

Mead is a fortified wine made with fermented honey. It was traditionally produced by the monks on Holy Island, but dates back further to the Roman period. Lindisfarne’s mead is unusual in that is uses grape juice mixed in with the honey, herbs and water.

You can try and buy local mead at St Aidan’s Winery (also known as Lindisfarne Mead) in the village. They’ve been making mead since the 1950s and also produce fruit wines and spirits, and work with a brewery in Alnwick to make a range of Holy Island beers as well as a dark Holy Island Rum which uses meadowsweet harvested from the island.

Coast walks

One of the best things about visiting Lindisfarne is soaking up the coastal views and the peaceful atmosphere. The island’s horseshoe-shaped harbour is home to a few small fishing boats. There are some larger ones on the water’s edge too, ingeniously recycled by being turned upside down and used for storage when they get too old to sail any more.

Once you pass the castle the island gets emptier, especially at high tide, as you head into the Lindisfarne Nature Reserve. Take a walk to see its sand dunes, windswept beaches and wildlife like deer onshore and seals offshore. You can also walk across to St Cuthbert’s Island at low tide, a tiny uninhabited island just off the southwest coast.

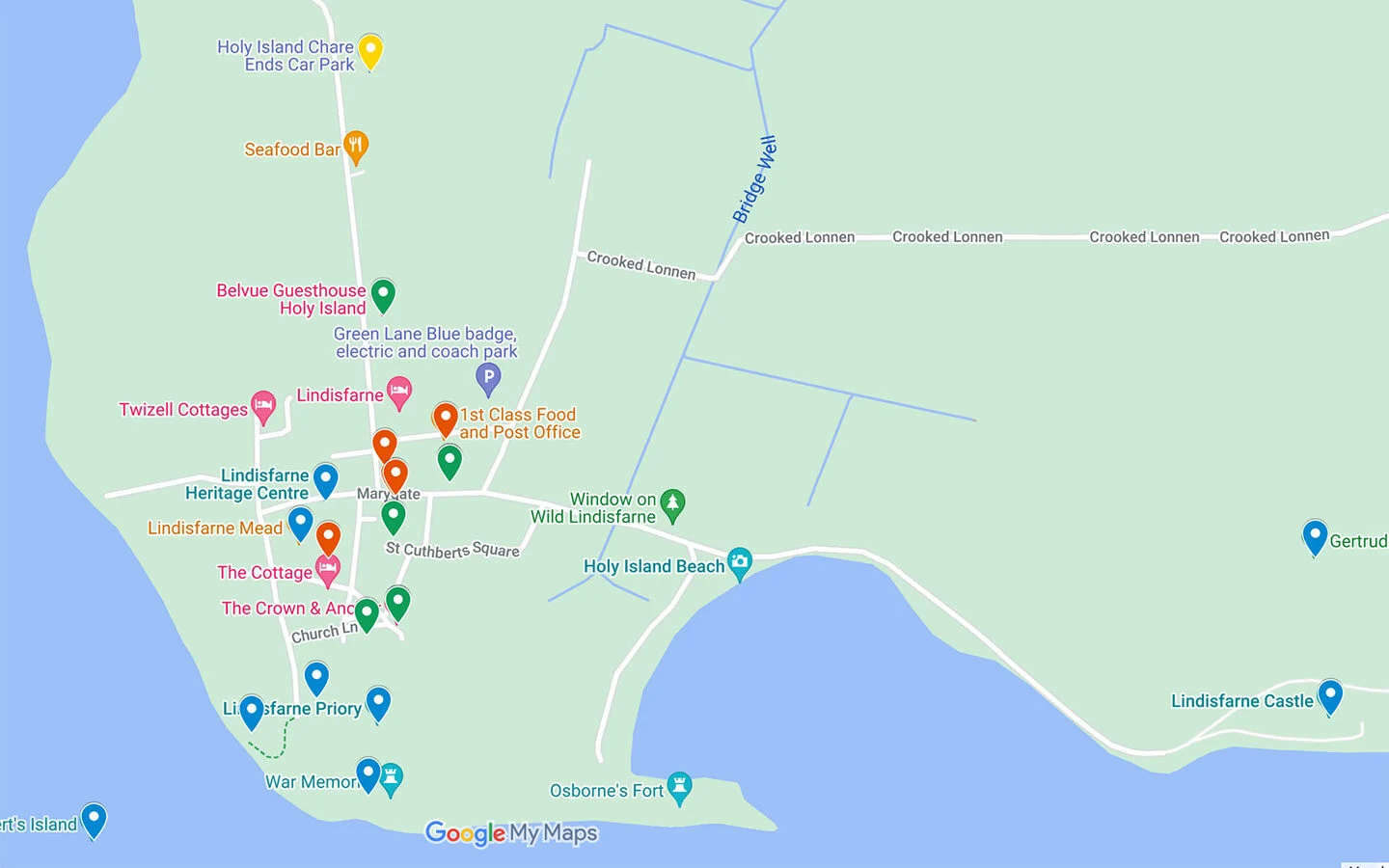

Map of things to do in Lindisfarne

Where to eat and drink in Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne has a small selection of cafés and pubs where you can get something to eat and drink. Space is limited though so it’s a good idea to make reservations, particularly for dinner in the high season. And beware that some places may close while the tide is in.

Pilgrim’s Coffee’s shop and roastery is hugely popular with coffee fans. They roast their own beans, which you can also buy to take away, and make tasty scones and cakes, including gluten- and vegan options like their fruity, flapjack-style Cuthbert Cake.

There’s also 1st Class Food at the post office and the Chare Ends Cafe, both of which serve breakfasts, sandwiches and cakes. You can pick up takeaway food like burgers, hotdogs and crab sandwiches from the Island Shack next to St Aidan’s Winery. And there’s homemade ice cream and fudge available from Pilgrims Fudge Kitchen and Gelateria.

The island has two pubs – the Crown and Anchor Inn and Ship Inn. The Crown and Anchor is dog-friendly and serves locally sourced dishes like fish and chips as well as veggie, vegan and gluten-free friendly options. The Ship Inn is a bit more of a traditional pub that does good real ales. Both also have beer gardens that are very popular in summer.

Where to stay on Lindisfarne

Staying overnight on Lindisfarne is a great way to experience the peaceful atmosphere without the crowds. The welcoming Belvue Guesthouse is one of the island’s top-rated places to stay, with two stylish studios with kitchenettes plus a budget twin room.

The Manor House Hotel* is the only traditional hotel on the island, and has the biggest selection of rooms, with 10 single, double, family and four-poster bedrooms. It’s right next to the priory and also has a bar and restaurant. The Crown and Anchor Inn and Ship Inn pubs also have four en-suite bedrooms each to rent on a bed and breakfast basis.

Or if you prefer self-catering, Eden Cottage* is a two-bedroom cottage which sleeps four, and comes with exposed beams, original stonework and a wood-burning stove.

Save for later